Twenty years after the worst attack to ever occur on U.S. soil, it's not just large, populated passenger planes that keep officials and experts up at night, but also the threat of smaller, readily available unmanned aerial systems capable of carrying deadly payloads through the skies of an unsuspecting nation.

Drones are not tomorrow's weapons of mass destruction. They're here today, and the technology required to fashion such a device is only getting cheaper, smarter and more accessible.

One U.S. military official who requested anonymity paints a potential nightmare scenario involving small drones, referred to as unmanned aerial systems, unmanned aircraft systems, or simply, UAS.

"I kind of wonder what could you do if you had a couple of small UAS and you flew into a crowded stadium," the U.S. military official told Newsweek. "That could cause a lot of damage and it's a scenario that could potentially be in play."

While "no specific knowledge" of an active threat was discussed, the U.S. military official said that "there is concern given the proliferation of small, portable drones, that explosive drones could cause a mass casualty event."

It wouldn't be the first time the nation had been caught off guard by a possible danger looming right in front of authorities.

"It's just like I had no specific knowledge before 9/11 that people could hijack planes and crash into buildings, but Tom Clancy wrote a book about it," the U.S. military official said.

When the political thriller "Debt of Honor" was released in 1994 depicting a hijacked airliner targeting the U.S. Capitol, the concept of an aerial suicide raid had largely been confined in the national consciousness to the experience of Japanese kamikaze pilots in World War II. It wasn't until nearly 3,000 were killed on September 11, 2001 that what had been an eventuality became a reality.

But when it comes to UAS, the age of tactical drone warfare is already upon us. Shortly after 9/11, the United States became the first country to truly weaponize drones, fitting them with precision missiles that became a staple of the "War on Terror."

In the years since, drones have evolved from a high-end military technology to a commercial hobby flown by enthusiasts across the globe and sold by a multitude of companies on the civilian market. With the explosion of this seemingly innocent innovation has come a rise in nefarious usage that the U.S. military official with whom Newsweek spoke described as "an emergent threat" already demonstrated in several high-profile events.

One such event came just last weekend when three explosive-laden UAS, believed to be simple quadcopter models, targeted the residence of Iraqi Prime Minister Mustafa al-Kadhimi in an assassination attempt. Kadhimi lived, but photos released of his home revealed the destructive capabilities of such devices.

Kadhimi was not the first world leader to be preyed upon by bomb-rigged UAS. In August 2018, two drones carrying explosives detonated in an apparent failed attempt to take out Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro during a military parade in Caracas. He also escaped with his life.

Prior to these incidents, militants and militias had already managed to utilize such technology, giving non-state actors a sort of rudimentary yet deadly air force to take on better-equipped foes. In Iraq and Syria, U.S. troops have been targeted from above by both the Islamic State militant group (ISIS) and Iran-aligned paramilitary forces.

Even more destructive platforms have seen action on the battlefield in the form of what's known as loitering munitions, or suicide drones. Last year, Azerbaijani forces demonstrated a deadly edge over Armenian rivals during a brief but bloody war over the disputed Nagorno-Karabakh territory through their use.

"They're relatively small, inexpensive drones, but they kind of cross that boundary between a drone and guided missile," the U.S. military official said.

This point was echoed by a security official from Israel, a country that produced some of the loitering munitions employed by Azerbaijani forces with substantial effect and now prove a potential concern for Iran as tensions simmer between the neighbors.

"This tool today is so easy, and small drones, you just really order them in and you've got yourself like a guided precision missile," the Israeli security official told Newsweek.

The Israeli security official noted that even with their current destructive potential, the munitions attached to such UAS today are in their relative infancy, not yet on a scale that any one of them alone could replicate a 9/11-style attack.

But their potential is already rapidly growing

"They are becoming much more accurate in their capabilities of navigation," the Israeli security official said. "I think where we will be seeing things is that the amount of explosives will get bigger now."

Smaller commercial UAS have another unique advantage over traditional aircraft and missile platforms: They have no launch signature, making them far more difficult to detect. Used in greater numbers, known as a swarm, they're also harder to intercept.

"If you need to intercept a dozen, an F-16 payload, if it's only doing air-to-air would be about six different air-to-air missiles, or similar to an F-35," the Israeli security official said. "So that already means that you need a few airplanes, and you need the time if you're looking at interception."

Israel was among the first nations to refine wartime drone technology, and it continues to field various platforms for covert missions. But its rivals have also demonstrated an early prowess for such technology, as proven by the Lebanese Hezbollah, the Palestinian Hamas, and their supporter, Iran.

Iran has developed an extensive arsenal of drones, including suicide drones capable of flying beyond 2,000 kilometers, exceeding 1,240 miles. Israel and the U.S. have both accused Iran of directly supplying UAS technology to partnered militias across the region, an allegation denied by the Islamic Republic.

"I think Tehran has its own independent defense program based on its defense needs and can define its efforts to counter the threats by strengthening its defense capabilities," an Iranian official told Newsweek.

China has also excelled in UAS technology, and Russia has developed high-end systems of its own as well.

The Israeli security official noted another trend that could prove deeply problematic to the safety of the region and beyond, a trend linked to Israel's ally, the U.S., and the withdrawal from a 20-year war in Afghanistan, where ISIS has sought to stage a comeback in a country the U.S. first entered in response to 9/11.

"We see another rise of terror, and I'll say, being both humble and appreciative to the U.S., but after Afghanistan, we do see a rise in what potentially could come again with the terror activities and the kind of backing that some of the terror organizations feel stronger and maybe even more courageous," the Israeli security official said. "This tool of drones can definitely be something that we might be seeing more."

One man who has written and spoken extensively on the potential impact of drones in the wrong hands is Zachary Kallenborn.

Kallenborn is a policy fellow at George Mason University's Schar School of Policy and Government and a research affiliate with the University of Maryland's Unconventional Weapons and Technology Division of the National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism. He has also served as a national security consultant and contributed to the U.S. Army as part of its Mad Scientist Laboratory.

"Drones are definitely capable of causing mass casualties," Kallenborn told Newsweek.

Echoing the example put forth by the U.S. military official with whom Newsweek spoke, he imagines a crowded event as a potential target.

"Growing drone technology also increasingly allows drones to be flown autonomously or in collaborative swarms," Kallenborn said. "That increases the damage potential significantly. Imagine a terrorist air raid: a group of drones dropping bombs on a concert or stadium crowd."

Even more damaging, attackers could vastly multiply casualties by employing weapons of mass destruction, Kallenborn warned.

"Drones would be highly effective delivery systems for chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear weapons," he said. "Drones could, say, spray the agent right over a crowded area."

Kallenborn said he was "also quite concerned about drone attacks on airplanes, because aircraft engines and wings are not designed to survive drone strikes."

But he notes that "who the attacker is matters a lot," adding that "a big limiter" for the worst-case scenarios "is the ability of terrorists to acquire the chemical, biological, radiological, or nuclear agent, which they have historically struggled with."

He pointed out the difficulty of a militant group acquiring both the material and manpower to fly a larger swarm-sized fleet while avoiding detection.

"But that limitation is not an issue for state militaries," Kallenborn said. "Militaries have the resources and technology to make truly massive swarms that could rival the harm of traditional weapons of mass destruction, including small nuclear weapons."

"Not only is such a weapon massively powerful, it would be quite difficult to control," he added. "If you have 1,000 drones working together without human control, that's 1,000 opportunities for failure. And even more, because in a true drone swarm, the drones talk. As we've seen with COVID vaccine paranoia, misinformation can spread easily even among beings far smarter than an algorithm-guided drone."

As humans and machines are wont to err, so are defenses, and drones add a new level of difficulty in their ability to conduct random, difficult-to-detect operations. The U.S. military official with whom Newsweek spoke expressed a level of skepticism regarding existing defenses being acquired by the Department of Defense.

"The DOD is pouring a lot of money and effort into counter-UAS technology, but I think the DOD's PR exceeds the actual capability of these devices," the U.S. military official said.

One of the agencies keeping an eye out for UAS and drone activity on the domestic side is the Federal Aviation Authority. An FAA spokesperson told Newsweek that "the FAA is tasked with ensuring the safety of the National Airspace System (NAS) as well as people and property on the ground."

"When criminal activity is suspected, we work with our federal, state, and local law enforcement partners by providing them assistance with their investigations and prosecutions," the spokesperson said.

One way in which the FAA is seeking to improve the ability for authorities to determine potential problems posed by UAS is by enforcing remote identification, through which drones would be required to provide key information such as identity, altitude and current location as well as the location of its operator and take-off point.

"Remote identification requirements for all UAS operators, when combined with our current registration requirement, will enable more effective detection and identification," the FAA spokesperson said. "This will also help law enforcement to connect an unauthorized drone with its operator. Remote identification will help law enforcement determine if a drone poses an actual threat that needs to be mitigated, or if it's an errant drone that got away from someone but means no harm."

The rise of the drone threat has given birth to a booming new industry of counter-drone technologies. Among the leading companies in this field is DroneShield, an Australian firm that has supplied cutting-edge tools to the likes of the NATO military alliance and the United Nations.

DroneShield CEO Oleg Vornik shared Kallenborn's concerns about WMD-strapped UAS in large numbers.

"Small UAS can be seen as a highly effective and cheap platform for surveillance and payload delivery," Vornik told Newsweek. "For payload delivery, a small UAS can easily carry up to a few pounds of weight — this is a lot of explosive or biological or chemical weapons."

"What's more," he added, "at $1,000-$2,000 per UAS, and swarming technologies available today (think of giant figures in the sky or fireworks, all generated by choreographed drones), this can be easily in 100s of drones, each carrying a dangerous substance."

These figures may seem high, but Vornik argued that the general lack of oversight would make it hard to track acquisition. And even if suggested controls were put in place, he said, the threat would only partially be addressed.

"UAS can be purchased today in a completely unrestricted way, being considered toys, essentially. Registration would solve some of the issue, but consider how many unregistered firearms get used for terrorism," Vornik said. "The pilot of the drone would also be invisible/difficult to catch in an attack, making it more appealing to use"

In addition to the kinetic threat, he warned of potential cyber attacks employing UAS

"Call it a conspiracy, but we received reports that the Ever Given container ship (yes, the one that blocked Suez Canal and stopped much of sea traffic) was due to a cyber hacking from a drone, when a request for ransom was denied," Vornik said. "We are now hearing of this commonly from ship customers, especially in areas close to the better-known rogue states."

Last week, DroneShield released the 6th edition of its C-UAS, or counter-UAS, factbook, which details the scope of potential threats posed by small drones.

The guide covers recent events in drone warfare, including the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict and the 2019 attacks on Saudi Aramco oil sites, claimed by Yemen's Ansar Allah, or Houthi, movement but blamed by Saudi Arabia and the U.S. on Iran. It also gives examples of the latest innovations by China and Russia, and identifies some of the most popular heavy-lifting UAS that could be used even more discretely than their larger cousins.

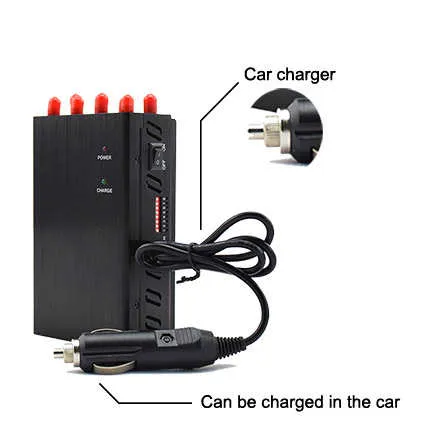

The report provides potential solutions as well, including a range of detection capabilities such as radio frequency, radar, acoustic, optics and multi-sensor systems. It also lists neutralizing assets including drone radio frequency jammer, GPS jammers, cyber tactics, directed energy attacks, counter-UAS drones and kinetic systems capable of blasting UAS out of the sky.

"Without dedicated C-UAS system (for detection and defeat of such UAS)," Vornik said, "there would be no warning and no time to react, until it is too late and the damage is done."

As to whether such tools and methods would be employed before the next attack, he has expressed a note of skepticism.

"We live in a reactive society," Vornik said. "Boulders across the pathways have only started to be placed after terrorists used vehicles to bulldoze through crowds, as an example."

He warned that governments and their law enforcement and security agencies must start setting up systems now to defend against UAS attacks.

"We need to be more proactive in setting up UAS detection and defeat systems across areas where large gatherings of people are likely, the high profile places, sort of areas which would be terror sweet spots," Vornik said. "Law enforcement and homeland security personnel need to be trained for this threat, much like more conventional attacks."