If you are searching for mobile signal blockers online, you may want to know the legality, price, and how to purchase them in the United States.

Continue reading to discover more information about these products. Here are some benefits of online purchasing:

Legitimacy of Mobile Phone Jammer in the United States

A recent case involving the legality of mobile phone jammers in the United States resulted in a Dallas company being fined $22000. This device is designed to interfere with wireless communication, including 911 and maritime and aviation communication. Unable to authenticate the device and does not comply with FCC technical standards. Therefore, selling or manufacturing these devices is illegal. However, there are also some exceptions to these rules.

The recent case involving two companies accused of illegally manufacturing and selling jammers is a good example. In one case, an electronic product manufacturer named RNM was found using cell phone blocker in their workplace. The FCC imposed a fine of $17000 on the company, plus $5000 for "bad behavior". Ravi's Import Warehouse received a notice of violation and requested the FCC Bureau to reconsider the decision. The FCC's law enforcement department rejected the request for reconsideration based on the company's compliance history.

The cost of mobile phone jammers

If you are looking for a phone jammer, you can find many options online. Many jammers aim to block one or more channels. More expensive models can block multiple signals simultaneously. You can also purchase a cheaper single channel blocker for only one signal. The cheaper models use battery power and can only cover very small areas. They are not as powerful as high-end devices, but they can still help you get rid of phone calls.

Before purchasing a mobile signal blocker, be sure to conduct some investigation. Firstly, you need to check the manufacturer. Find someone who uses three watts of power. Ensure that the jammer is suitable for all major networks. This will ensure that you receive the best value for money product. If you are worried about attracting thieves, please consider investing in a device that can block signals.

May 14-May 20, you can get 10% OFF

Purchase mobile phone jammer

Buying a mobile phone jammer online is not difficult. This will cost you hundreds to thousands of dollars. Their working principle is to block all forms of cellular signals, including mobile phone signals, WiFi, GPS signals, and police radar. Buying and operating them is illegal, but some people still do so. In 2014, a Florida man was fined $48000 for using GPS jammers at work, and a truck driver was fined $32000 for using GPS jammers at the airport. Fortunately, these two situations are rare.

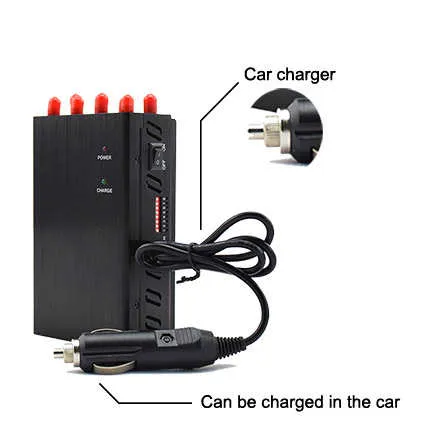

Before purchasing a mobile phone jammer, be sure to conduct research. Most jammers on the market are illegal, so it is important to carefully study them. It may backfire and disrupt your provider's network. Due to the fact that most mobile phone signals are weaker in rural areas than in urban areas, you need to carefully position your device. You can purchase portable devices, car gps jammer, or fixed jammers. Before purchasing a jammer, be sure to check the safety seal on the product.

Mobile network interceptor GSM CDMA 3G 4G GPS, VHF, UHF, WIFI signal jammer

The supplier of mobile signal blockers offers a variety of models, which are very suitable for use in conference rooms, meeting areas, offices, and other spaces. These products can block GSM, CDMA, GPS, VHF, and WiFi signals and can be easily hidden in rooms or vehicles. Each model has a separate frequency control switch that can identify up to 8 active IMSIs and prevent them from receiving signals.

Its high output power jammer has an interference range of 200-300 meters, strong interference ability, and is easy to carry. The jammer adopts an advanced cooling system that can work continuously for a long time and is equipped with a sturdy portable box. This type of jammer can also interfere with six different frequency bands, which allows it to effectively block various mobile phone signals.

GPS signal blocker

The GPS signal blocker has a small size and exquisite workmanship. It aims to block all current GPS signals without interfering with the normal use of electronic devices. It can be applied to various types of locations. Dual channel shielding technology is more reliable and secure than single channel shielding. This GPS signal blocking device is designed to block signals from mobile phones and GPS devices. This product is easy to use and can be used for various settings.

GPS signal blockers can be used for different purposes, such as home or car safety. It can work independently and simultaneously, creating a shield radius of up to 40 meters. GPS signal blocking devices can block signals from cellular or WiFi networks. It can also protect cars from theft. GPS signal blocking devices are very useful for children, but installing one of them in a car is illegal.